CHRISTINE HOGG

Originating in the Middle Ages, Benedictine monks were the first to start churning out large wheels of cheese with a long maturation period, using salt from Salsomaggiore salt mines and fresh cow’s milk. Free from additives and preservatives, the longer the cheese aged, the more value it held. According to the consortium Parmigiano Reggiano, which was founded in 1901 in a bid to authenticate and differentiate between copycat Parmesan cheeses, the first evidence of cheese being used as commerce through trade dates back to a record of sale in the 12th century.

From dowries to land agreements, cheese was used as a form of currency for hundreds of years.

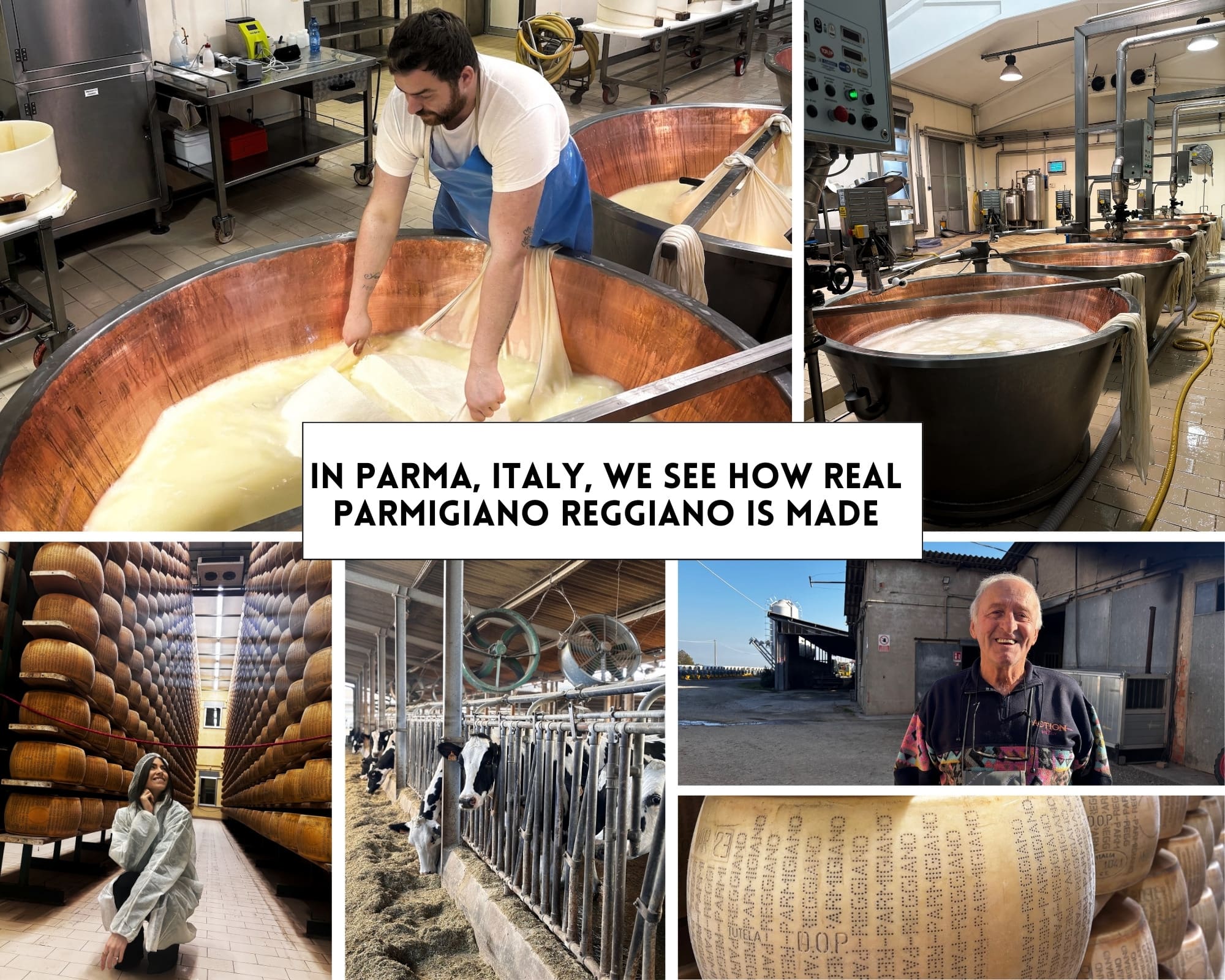

On a visit to Parma, Italy, I’m learning firsthand how one of North America’s most beloved cheeses gets into our grocery stores and grated onto our plates. And make no mistake—this cheese is nothing like the imitation stuff in plastic shakers.

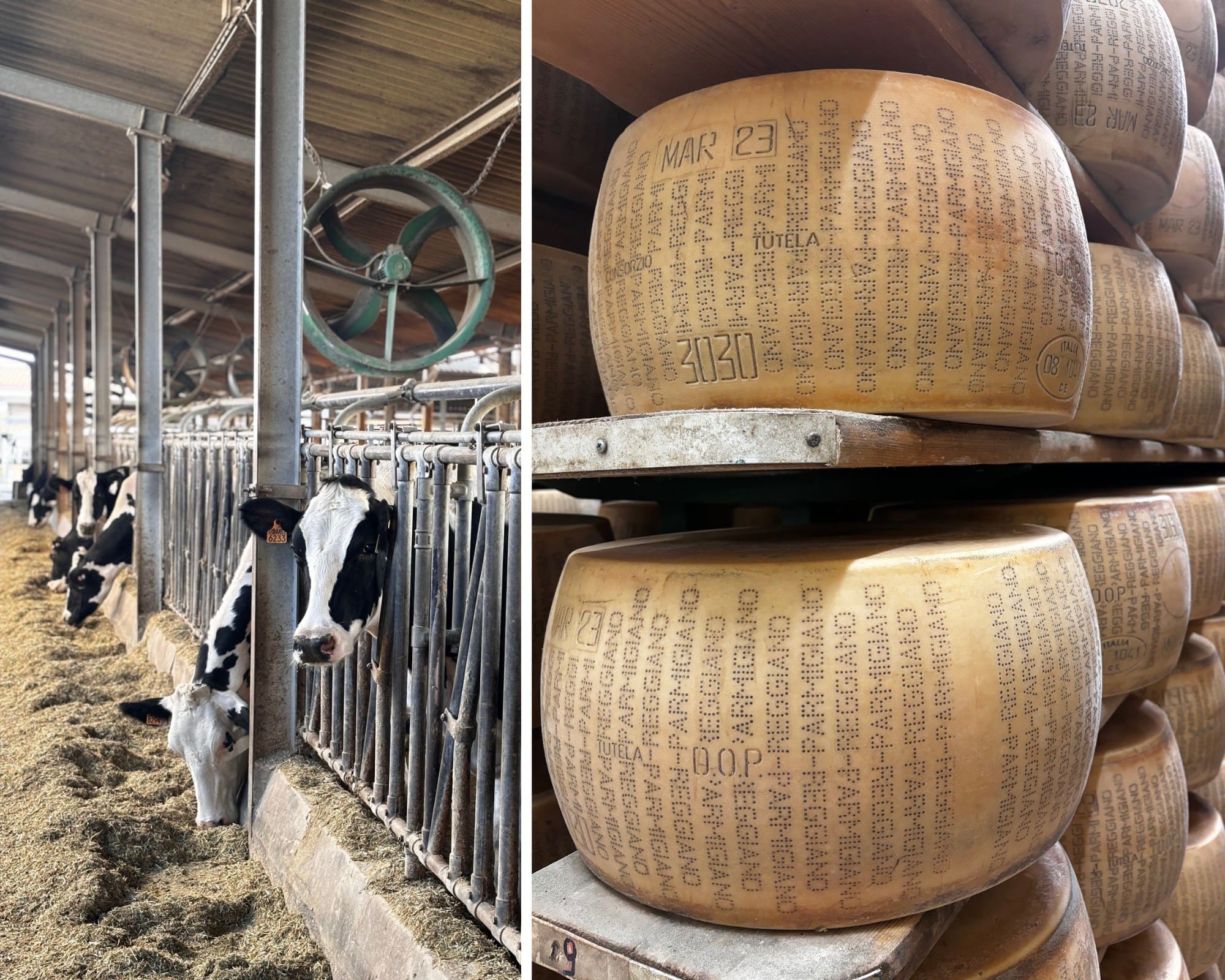

At Azienda Agricola Bertinelli, a producer of Parmigiano Reggiano, the process starts with roughly 550 litres of raw milk. “Half of the milk is from the previous evening that is kept in large containers and half is from this morning,” says Giovanna Rosati, spokesperson for the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium. “In the morning, they push the container over the vat and the partially skimmed milk falls into the vat. They are not allowed to use a decreamer, because it would alter the milk. It’s a great example of a protected designation of origin (PDO) product.” From there, rennet (an enzyme found in the stomach of dairy cattle) is added and the milk begins to naturally curd.

Next, it’s the job of the master cheesemaker to break the curd down and begin cooking the cheese. “You’ll always be able to recognize the master cheesemaker, because he or she is the one supervising the cooking process,” says Rosati. In this case, he’s the son of Gianni Bertinelli, owner of Azienda Agricola Bertinelli and a fifth generation producer. Using steam, the curds sink to the bottom of the vat and begin to form one giant mass. From start to finish, the process takes roughly 50 minutes, in which two twin wheels of cheese are created.

But the work doesn’t stop there. After cooking, each cheese is wrapped in a traditional linen cloth, then placed in a traditional mould, which gives it its classic wheel shape. Next, it’s transferred to a casein plate, which is outfitted with a sequential alphanumeric code that enables the cheese to be traced all the way back to its origins.

“It’s like a license plate,” explains Rosati. “This afternoon, they’ll remove the linen cloth the cheese was wrapped in and the casein plate, and place it in a stenciling mould.” Holding up the stencil, Rosati looks almost like a WWE wrestler with the prized championship belt. “This engraves a few key details on the rind of the cheese,” she explains, noting it includes the code of the dairy producer where the cheese was made, as well as the month and year of production.

To be classified as a true Parmigiano Reggiano product, the cheese must be aged for a minimum of 12 months and undergo a rigorous quality control check, which includes a series of tapping tests to check for air pockets or tears.

And as for the cheese that doesn’t pass the test?

It’s cut up and sold as regular Parmesan—not to say that it isn’t outstanding, but without that stamp of approval, it’s no Parmigiano Reggiano.