TED DAVIS

A growing recognition of civil rights sites of significance in America is giving more options and opportunities to travellers, both domestic and international. That turbulent period of struggle against Black oppression in America is a subject of ongoing exploration. This has rendered tributes like museums and memorials that can be seen and experienced by travellers keen to learn more.

Some of these are included in the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, which showcases many of the most important landmarks in U.S. civil rights history, says Brand USA, the nation’s destination marketing organization. Seemingly innocuous spots like a church or high school or bridge have become key locations on the trail, which is a living catalogue of the civil rights movement.

One of those places is in Selma, Alabama. The Edmund Pettus Bridge is where, in 1965, civil rights protest marchers faced off against a force of state troopers, resulting in attacks and beatings. The Selma Interpretive Center has announced that work on a US$20 million addition will start next year. The center, located at the foot of the bridge, marks the beginning of the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail.

Another important site is in the city of Mobile, AL. Last year marked the opening of “Clotilda: The Exhibition,” which tells the story of the last known slave ship to reach American shores, with its cargo of 110 slaves captured from West Africa. The sunken schooner was found at the bottom of the Mobile River in 2019, and has since been salvaged for historical artifacts in the following years.

The results of that work are showcased in the exhibition, including pieces of the actual ship, and everything from carved masks to woven patterns. The exhibition covers about 230 square metres and “is a rich, multi-sensory space, dense with compelling stories and images.”

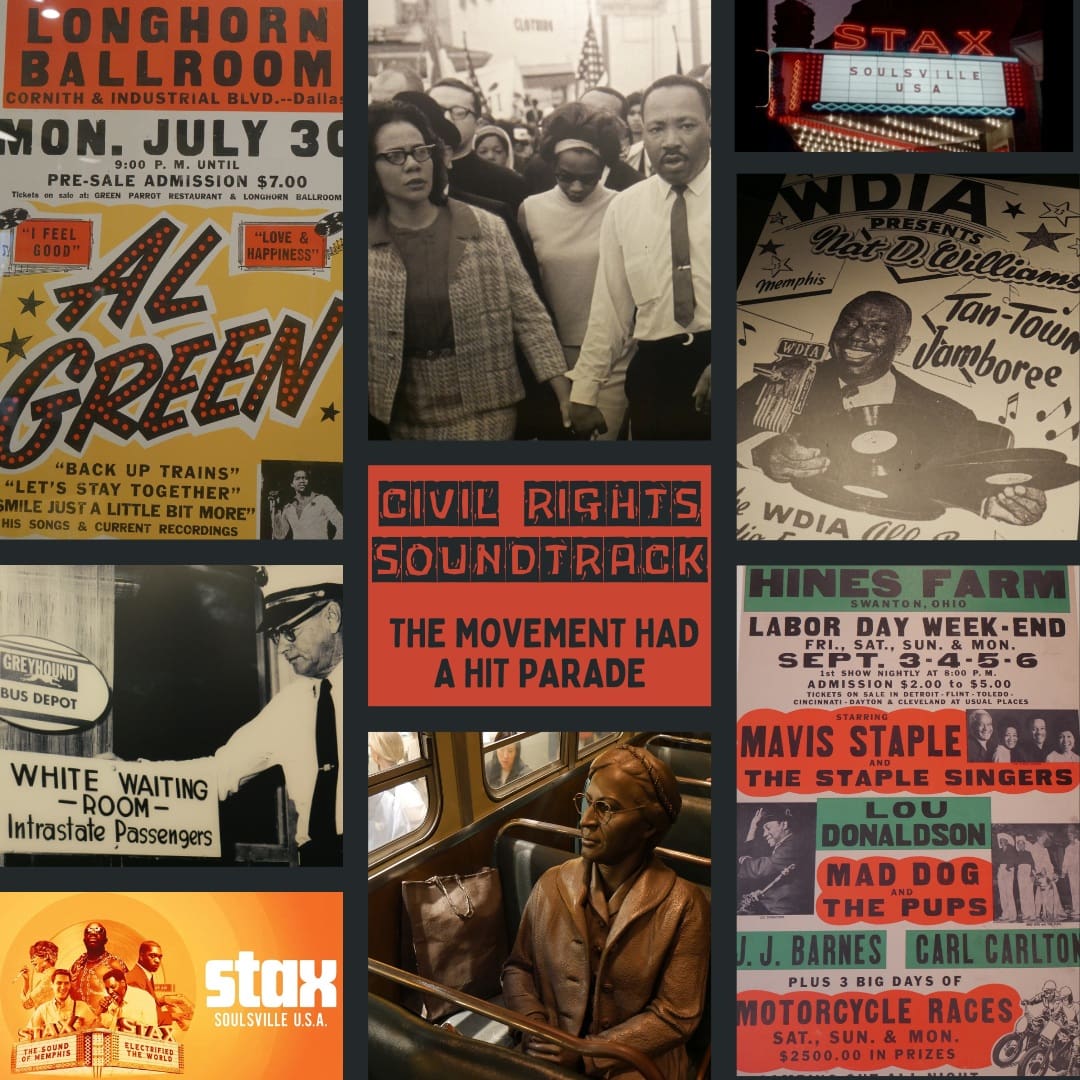

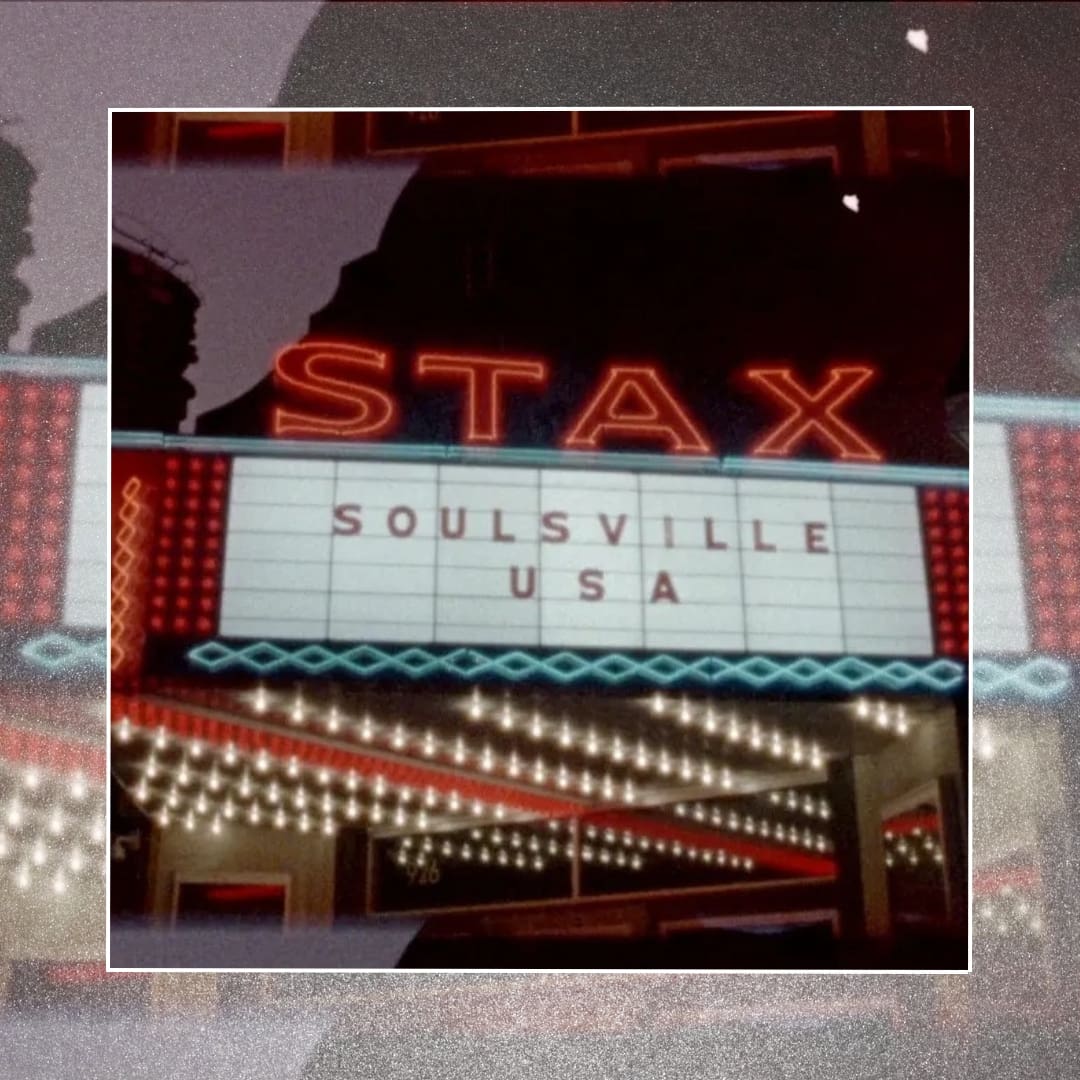

But only one place has won the recognition of an HBO documentary mini-series – Stax Records of Memphis. This four-part, four-hour program is named “STAX: Soulsville, USA” and it first aired in May of this year.

The show chronicles the quick rise and fall of a company that developed and recorded some of the most influential Black musicians of the 1960s and ‘70s. Founded in 1957, Stax Records recorded the likes of Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave, Albert King, Otis Redding and Isaac Hayes.

It did its part to bridge the civil rights barriers by forming bands that used both Black and White musicians, an uncommon practice in those days of unrest. It was “an oasis of racial sanity within a segregated society,” says a Stax history.

Hence for example the in-house Booker T and the MGs band, led by Booker T. Jones (a Black) and composed of players of both sides of the racial divide. Booker T and the MGs backed most of the musicians in the Stax stable, and scored their own hit with the instrumental “Green Onions,” which climbed the charts on both Black and White radio.

One of the most successful of all the racial crossovers by Stax was “Soul Man” by Redding, which was propelled to further popularity by the singer’s appearance at the massively successful Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. Another huge hit for Stax – and amongst its last – was the “Theme From Shaft” by Issac Hayes, in 1971.

There were more strident political statements made by Black musicians from other studios in America, including Motown Records in Detroit. Its roster of artists included The Temptations (Ball of Confusion), Edwin Starr (War), and Marvin Gaye (What’s Going On).

But the political stance by Stax was to lead by example, by being more racially integrated in the production of its music. Its practice to generate more Black/White collaborations was a rarity in the southern USA.

Some of this territory is well covered in the HBO docu-series, including the rise to super-stardom of Otis Redding and his untimely death in a plane crash in 1967. The documentary also unearths a trove of rarely-seen or never-seen footage, including home movies by Stax intimates, film clips of scenes in the recording studio and 16mm film imagery of street life in 1960s Memphis.

But the best way to experience the music of Stax is in person, at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis. Visitors follow a winding exhibition corridor that details the unfolding history of Stax in chronological order, told through lots of photos, posters, musical artifacts and written descriptions. It is a revealing walk for music lovers, supporting the declaration that the music from Stax and other studios like Motown Records were instrumental in the civil rights struggle.

NATIONAL CIVIL RIGHTS MUSEUM

Five-plus decades ago, the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis was a favourite hang-out for the Stax employees, and for the musicians who were in town for recording sessions. It was just three km. from Stax and was one of the few places where the integrated staff could gather to socialize, have a swim and eat authentic soul food. Songs were even created and composed there, including the Wilson Pickett hit “In The Midnight Hour.”

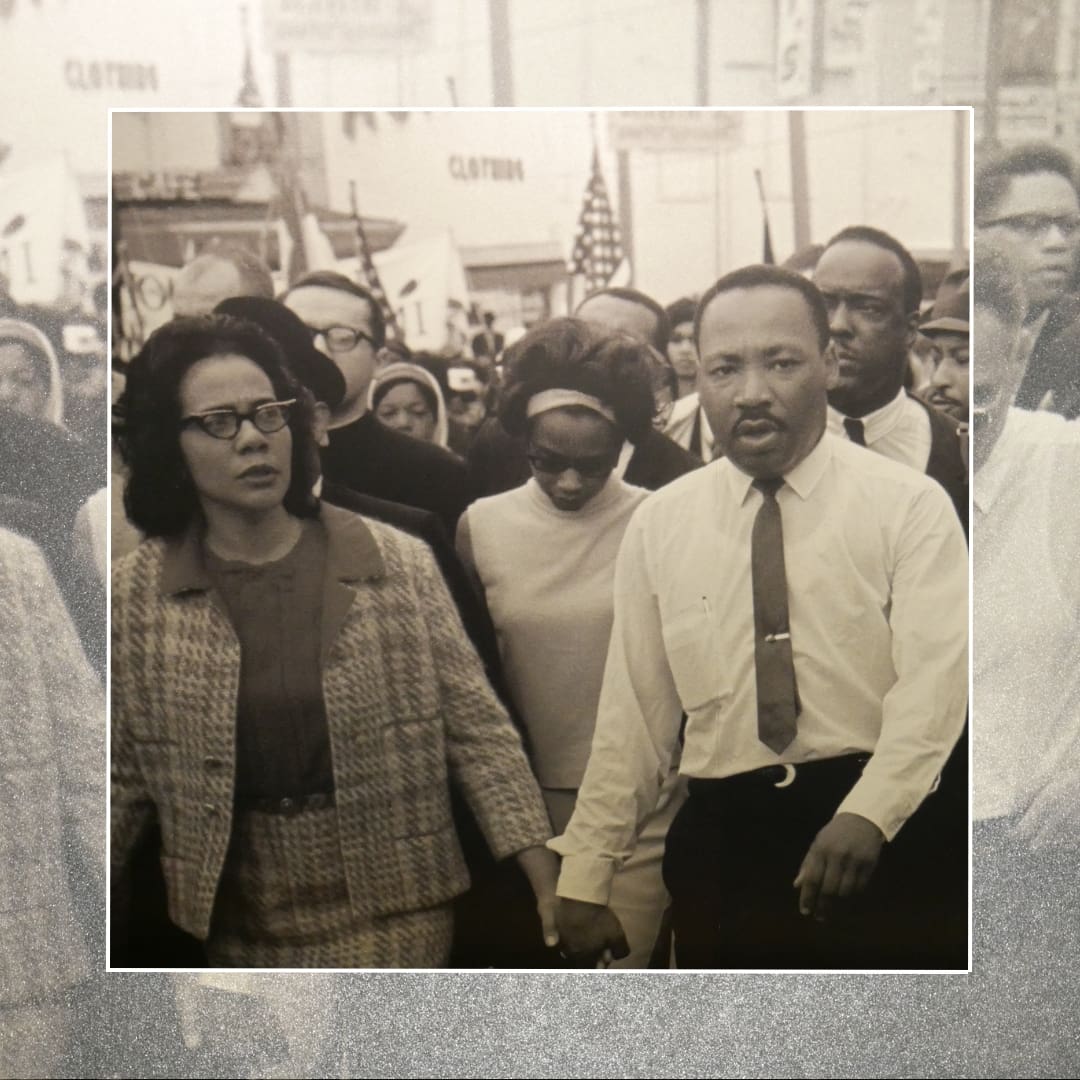

That all changed on April 4, 1968, when Dr. Martin Luther King was shot while standing on a second floor balcony of the Lorraine Hotel. The charismatic leader of the civil rights movement in America was dead, and more racial turmoil threatened to sweep through the country.

These momentous events, including the rise of Dr. King to prominence, his leadership contributions to the movement and other chapters in the civil rights struggle are commemorated at the Lorraine Hotel – which was converted to the National Civil Rights Museum in 1991, and fully renovated in 2014.

This comprehensive tribute museum his chronologically organized, so that the earliest moments of the African slave trade economy are described through written explanations, paintings, films and interactive mediums. This history of slavery is followed by further chapters, including the Jim Crow era, segregation and depictions of key civil rights events, such as the refusal by Rosa Parks to obey orders to vacate her seat on a city bus in Montgomery.

Touring the National Civil Rights Museum is an instructive, sobering stroll. It concludes with entry to the original hallway of the hotel and views of the small rooms where King stayed. The balcony where King was shot has also been preserved, as has the motel façade and the parking lot below the balcony, complete with a 60s-era Cadillac. A plaque in the parking lot describes the scene, providing a very effective conclusion to a tour of the museum.

Memphis has other musical sites of significance, most notably Sun Studio and the former Elvis Presley estate of Graceland, but these did not play roles in the evolution of civil rights.

SLAVE HAVEN UNDERGROUND RAILROAD MUSEUM

A more relevant location to complete an exploration of civil rights in Memphis is to go back to the slave origins of the conflict, at the Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum.

This is an original refuge house for slaves who had escaped their owners and were on the run to reach a freedom destination in the north – either a state that had banned slavery or even Canada. The small, two-storey house sits in an unremarkable neighbourhood, about three km. north of downtown Memphis and importantly, a short distance from the banks of the Mississippi River.

Travelling by night, escaping slaves could stow away aboard river boats that were sailing on the Mississippi. They would have had some information on refuge stops enroute, including this one – the Burkle Estate, built in 1849 by a German immigrant.

Its principal hiding place was a crawl space under the ground floor, accessed by a small hinged door in the wooden plank floor. Runaway slaves would apparently hide in this dark cellar until an opportunity to continue their flight north. It was a tight fit and can still be seen on tours of the house.

The secret mission of the Burkle Estate was only fully revealed in the 1970s and it is regarded as the sole Underground Railroad house still existing in the Southern U.S. The museum is temporarily closed due to a recent fire.

As a final nod to this musical theme, it is worth noting that crucial information about the Underground Railroad routes was passed along between slaves while they worked in the farm fields of the South. To avoid being noticed, and punished, this information was delivered by the singing of songs, coded as spirituals. The civil rights soundtrack had its roots in the slave trade of early America.